Photo credit: Daniel Garcia

Drought in Uruguay: Foresight, overconfidence and electoral calculations

Never before have Uruguayans been so aware of weather forecasts, nor have these reports occupied so much time on radio and television news. It is not for nothing. The country is still going through the worst drought in the last 80 years, and although it has passed an extremely critical moment, it is still far from returning to “normal.” This new normal is the subject of much debate.

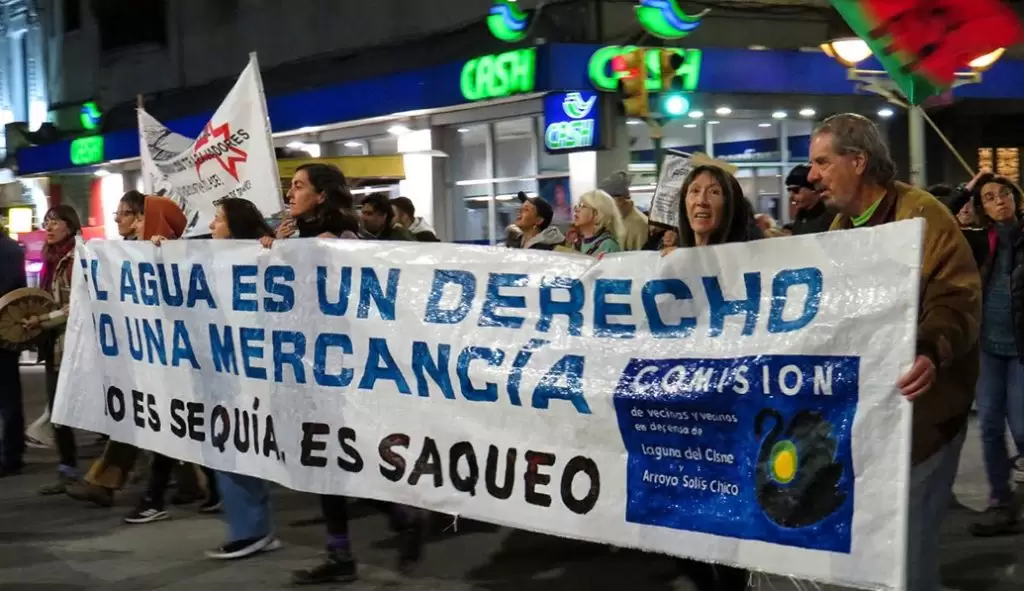

“It’s not drought, it’s looting” goes the slogan of numerous civil society and trade union organizations that have mobilized to denounce a production model that “confiscates” water for the benefit of large agricultural and industrial companies to the detriment of the community. But this reality only burst into the general consciousness when water became an asset in daily dispute.

Montevideo and its “metropolitan zone,” where almost two thirds of the country’s population is concentrated, have a single source of water (the Santa Lucía River) and a relatively small reservoir in the Paso Severino dam.

The traditional undulating and bucolic meadows housing four cows per inhabitant have been gradually adopting new methods of production.

Currently, 80% of fresh water is used in agricultural activities: rice, wheat, dairy, and more recently soybeans, and industrial forestry that serves three pulp mills, two of them the largest in the world. In general, these activities do not pay for the fresh water they consume.

Added to the more intensive use of land and water is the massive application of chemicals that have polluted streams and rivers, which notoriously altered the quality of water for human consumption: for years many homes and workplaces have installed filters or consume bottled water. It means that this “water crisis” is not really a surprise.

Here we also ignore the signs of transformation of the production context, of climate change, of the stress caused to nature that was imagined inexhaustible. The necessary works to consolidate the water supply system for the capital and its surroundings were not carried out, the conditions of a perfect storm converged, and the rain stopped falling on our heads.

The government was slow to react and waited until the last moment to implement palliative measures. For more than two months, the water that flowed from the tap had high sodium and chloride contents, which transformed it from “potable” to “drinkable,” according to the curious definitions of the government, a consequence of the fact that water from the Río de la Plata was used, usually a mixture of sweet and salty.

Bottled water consumption increased exponentially and social services implemented subsidies for the most vulnerable families so that they could purchase water.

For many, it was no coincidence that a private project to complement the capital’s water supply system called “Proyecto Neptuno,” at a cost of 500 million USD, gained notoriety, while the government dismissed the construction of a new state dam whose financing was already approved by the previous government.

Since then there has been some rain but not much. In the faucet the water recovered its usual flavor, but for how long, we do not know. The political system seeks, without too much zeal, to shape a State policy around drinking water, knowing that next year is an electoral year when there will be many accounts to settle, many promises to make, many slogans to wave.

The drought has so far cost some 2 billion USD in expenses and decreased production. For some experts it is only the beginning in the cycle of droughts and floods that climate change will impose. The warning is over.